We've just released an updated version of the dataset:

Physion V1.5

Click here to learn more

Do today’s vision models understand everyday physical phenomena as well as people do?

Physion is a dataset and benchmark for evaluating AI models against human intuitions about how objects move and interact with one another. We test a broad suite of state-of-the-art models and a large number of people on the same 1.2K examples of objects rolling, sliding, falling, colliding, deforming, and more. We show that humans surpass current computer vision models at predicting how scenes unfold. Our experiments suggest that endowing these models with more physically explicit scene representations is a promising path toward human-like physical scene understanding, and thus safer and more effective AI.

Watch our talk at NeurIPS 2021

Probing physical understanding in machines

Almost all of our behavior is guided by intuitive physics: our implicit knowledge of how different objects and materials behave in a wide variety of common scenarios. We know to stack boxes from largest to smallest, to place a cup on its flat base rather than its curved side, and to hook a coat on a hanger, lest it fall to the floor. As AI algorithms play a larger role in our daily life, we must ensure that they, too, can make safe and effective decisions. But do they understand the physical world well enough to do so?

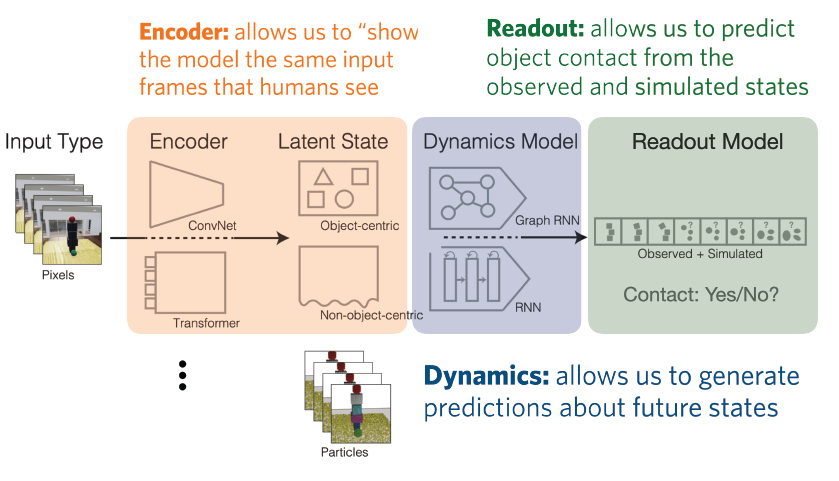

To answer this, we need a way of “asking” an AI model how it perceives a physical scenario. Two approaches have been popular in prior work: (1) asking models questions about simple scenarios, such as whether a block tower will fall or an object will emerge from behind an occluder; and (2) training and testing large neural networks on video synthesis, i.e. asking them to predict the upcoming frames of a movie.

Each of these approaches has merits and drawbacks. The first dovetails with research in cognitive science, which has found that people make accurate predictions about key physical events, like the tower falling, while abstracting away low-level details. To date, however, this sort of benchmarking in AI has been restricted to a few simple scenarios that lack the variety and complexity of everyday physics.

The second approach makes few assumptions about how an algorithm should understand scenes. For this reason, video synthesis on real, unlabeled data is a popular training task in robotics: if an agent can make accurate predictions about its environment, it might accomplish its goals. But predicting everything about how a scene changes is enormously hard, even with gargantuan datasets. As a result, these models currently succeed only in narrow domains. Moreover, humans do not even see everything that happens in a movie, let alone predict it; video synthesis is therefore unlikely to capture the intuitions we use to make decisions in new, wide-ranging settings.

Physion: a benchmark for visual intuitive physics

To fill the large gap between these approaches, we need a way to test for human-like physical understanding in diverse, challenging, and visually realistic environments. We therefore introduce the Physion Dataset and Benchmark. Our key contributions are:

- Training and testing sets for eight realistically simulated and rendered 3D scenarios that probe different aspects of physical understanding: how objects roll, slide, fall, and collide; how one object may support, contain, or attach to another; and how multiple objects made of different materials interact,

- A unified testing protocol for comparing AI models to humans on a challenging prediction task,

- An initial evaluation of state-of-the-art computer vision and graph neural network models on the Physion benchmark, the results of which suggest that today’s algorithms should incorporate more physically explicit scene representations to reach human ability.

Using ThreeDWorld to design the benchmark

On a narrow benchmark, models might overfit and achieve “super-human performance” without understanding everyday physics in the general, flexible way people do. On the other hand, a benchmark that relied on higher level “semantic” knowledge would not directly test intuitive physics. We therefore took an intermediate approach to designing Physion: each of its eight scenarios focuses on specific physical phenomena that occur often in everyday life. Stimuli for each scenario were physically simulated and visually rendered using the Unity3D-based ThreeDWorld environment, which adeptly handles diverse physics like projectile motion and object collisions, rolling and sliding across surfaces of varying friction, and clothlike or deformable material interactions. We provide training and testing sets of 2000 and 150 movies, respectively, for each scenario, as well as code for generating more training data.

Comparing humans and machines

To measure how well both models and people understand each scenario, we created a common readout task for all stimuli: Object Contact Prediction. This task has a person or model observe the first portion of each Physion movie, then make a prediction about whether two of the scene’s objects will come into contact during the remaining, unseen portion. People easily grasp this task and make accurate predictions. To measure model behavior, we adapted the standard method of transfer learning to our prediction task: models pretrained on unlabeled Physion movies or other datasets are probed with a linear readout to make predictions about upcoming object contact. Since models and humans do the same task on the same stimuli, we can directly compare their behavior.

How do today’s AI models compare to humans?

Humans make accurate predictions about the Physion stimuli, but they aren’t perfect. Some scenarios were more challenging than others: for instance, people had a harder time judging the effects of object-object attachment in the Link scenario than how objects would fall down a ramp in the Roll scenario. Moreover, some stimuli appeared to be “physically adversarial”: most people predicted one outcome, but in the ground truth movie the opposite occurred – often due to a physical fluke, like an object teetering on the brink of falling over. Imperfect human performance is a feature of our approach, not a bug: it means that a (hypothetical) super-human model might be overfitting to scenario-specific cues that people ignore. Since abstracting away low-level detail is key to how we make general and efficient judgments, it is crucial to know whether current and future AI models do the same.

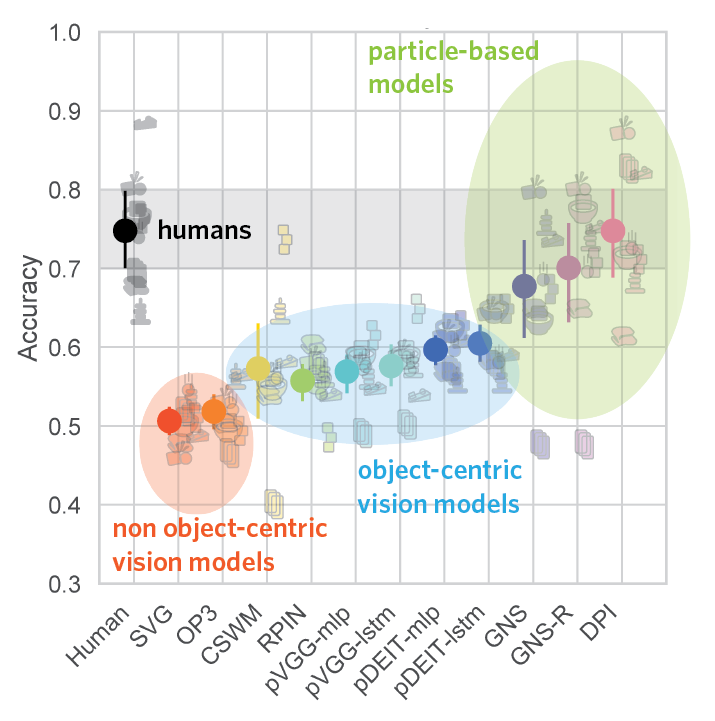

For the time being, though, the state-of-the-art in computer vision appears to be far behind humans at making physical predictions: none of the vision neural networks we tested, regardless of model architecture or pretraining task, came close to human performance on the Physion benchmark. While the models that received object-centric training signals fared slightly better than those that didn’t, control experiments suggested that these models often fail to make human-like judgments about what they observe, even before making predictions. Thus, current vision models appear to lack essential components of human intuitive physics.

What’s missing from vision algorithms to achieve physical understanding?

Fortunately, the way to close this large gap between models and machines isn’t a total shot in the dark: in some cases neural networks did perform as well as people. Several Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) reached human accuracy on some Physion scenarios, suggesting that they may hold aspects of intuitive physical understanding. However, these models have an enormous advantage over people: instead of receiving visual input, they operate on the ground truth physical state of the ThreeDWorld simulator. This means that they have near-perfect knowledge of each object’s boundaries, 3D shape, and fine-scale trajectory; are unhindered by occlusion; and are explicitly told which parts of the scene can be ignored or compressed into a more efficient representation.

Thus, these models bypass the amazing computations our brain uses to parse a scene as a set of physical objects moving through 3D space – computations that emerge, without direct supervision, by the end of human infancy. The GNNs’ success suggests, though, that if we understood these computations – that is, if we could implement visual encoding models that produce object-centric, physically explicit scene representations – then we might obtain algorithms with (more) human-like physical understanding. Such vision models are therefore an attractive target for future work and for using Physion to bring AI in line with our intuitive physics.

Physion Gallery

Below are several example videos from each scenario class, varying in prediction difficulty for humans from the most difficult (top row) to least difficult (bottom row).

Support

Roll

Link

Drop

Dominoes

Contain

Collide

Drape